Monthly Archives: April 2008

Getting it wrong

The other day I wrote about the importance of getting it right.

You’re also free, I think, to get it wrong – even in a historical novel. Different writers have different thresholds, of course, but even the strictest acknowledge that when it comes to fiction it’s the story that really counts. Joan Aiken wrote a terrific series of historical novels for children, set in an 18th century England where the House of Stuart still reigned: she got it wrong, but it felt absolutely right. What’s important is consistency.

In the Yashim stories I wouldn’t go that far. It is 1836, or 1840, and the sultan is the sultan. Venice is under Austrian occupation. You could buy champagne in Pera, on the shores of the Golden Horn. Gentile Bellini was, indeed, invited to Istanbul in 1479, where he painted a portrait of sultan Mehmed II. These, to me, are the Big Facts. There are lots more, and half the fun is weaving one’s imagination around them.

So one of my favourite characters is the validé, the sultan’s mother, whose astonishing story – from French ingénue to harem queen – is brilliantly recounted in Leslie Blanche’s The Wilder Shores of Love. She is Yashim’s friend in the palace. He appreciates her dry cynicism; she relishes his lurid tales from the City; and they share a fondness for Parisian novels.

But in truth, her presence in the harem is a matter of historical speculation, not certified fact, so no-one can say for sure whether she became the mother of Sultan Mahmud II. Either way, Mahmud’s mother was certainly dead by 1818: you can visit her tomb in Istanbul.

In The Bellini Card, set in 1840, she puts Yashim on the right track. She is very old; she is also very clever.

I wouldn’t lose her for the world.

Getting It Right

Nothing breaks the mood like a duff note – a glaring anachronism, a remark made in inappropriate slang, or the moment when your character’s eyes change mysteriously from blue to brown.

On the other hand, it’s important not to get too bogged down in verifying details when you’re writing. After all, it’s the story that counts, isn’t it?

Copy editing – which we’re doing now with The Bellini Card – is the proper time to address those niggles.

Is the name of the street spelled correctly? Do baby artichokes come into market before the asparagus?

Last week I even asked a fencing master round for tea, and we discussed the swordplay I’d written for the Contessa. It has been years since I fenced – sabre, not foil – but it turned out I’d got it almost right, except for calling octave optime; and he had a nice riff for me about a beat to the blade…

So The Bellini Card even has a fight co-ordinator!

On the question of slang, I gave some minor characters in The Janissary Tree Cockney accents. I wanted to show that they were working men and women who’d grown up on the city streets: Istanbul, of course, not London. I think it was the right choice – I’m writing in English, after all. Decide for yourself, maybe.

I just checked with a friend whether women were able to work as calligraphers in the Ottoman Empire, transcribing the Koran.

My answer arrived by email: a beautiful Hilya – a calligraphic portrayal of the Prophet – by an 18th century woman calligrapher, Esma Ibret.

The Polish Ambassador

Stanislaw Palewski is the Polish ambassador in Istanbul, Yashim’s old friend.

Here’s how he appeared in The Janissary Tree:

Yashim and Palewski were unlikely friends, but they were firm ones. ‘We are two halves, who together become whole, you and I,’ Palewski had once declared, after soaking up more vodka than would have been good for him were it not for the fact, which he sternly upheld, that only the bitter herb it contained could keep him sane and alive. ‘I am an ambassador without a country and you – a man without testicles.’ Yashim had pointed out that Palewski might, at a pinch, get his country back, but the Polish Ambassador had waved him away with a loud outbreak of sobs. ‘About as likely as you growing balls, I’m afraid. Never. Never. The bastards!’ Soon after that he had fallen asleep, and Yashim had employed a porter to carry him home on his back…

My children found this image on the net: I think it could be him.

What do you think?

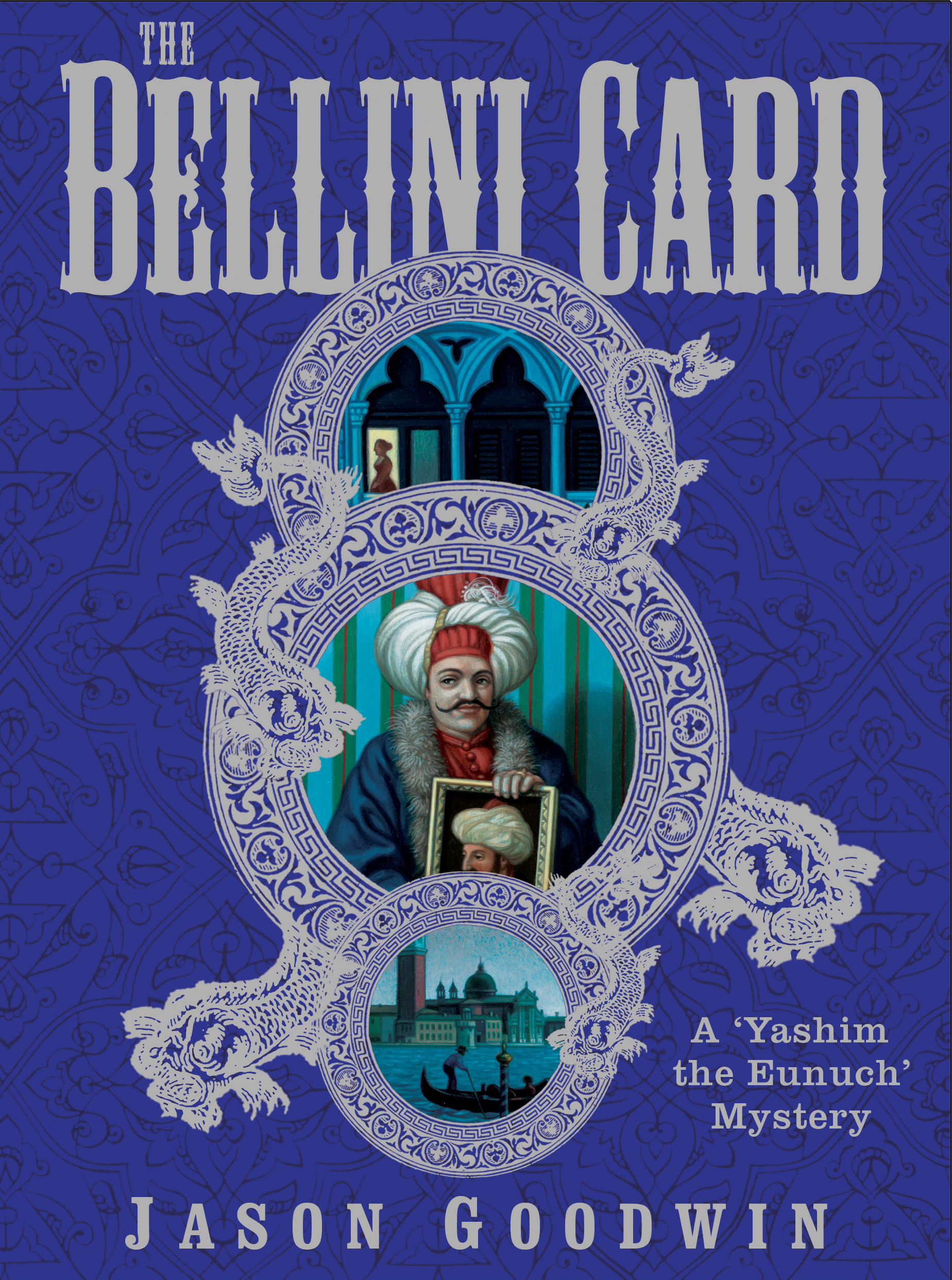

Judging a book by…its cover

Faber’s artwork for the UK edition has popped up on my screen! I like it enormously, just as I liked the covers of the first two Yashim novels, The Janissary Tree and The Snake Stone. They manage to look period and fun at the same time: bold colours, strong motifs, and a striking family resemblance, too. I get the feeling that the designers enjoyed themselves here, don’t you?

A silhouette in a lighted window. A gondola. And a man in an extravagant turban, clutching a painting. It’s as if clues are being dropped even before you open the book.

The End

Link here to www.jasongoodwin.net.

You know your book’s done when those two words appear at the bottom of the page.

Triumph – or disaster?

I can’t tell. Sometimes I think that finishing a book is the literary equivalent of a one-night stand: breakfast is yet to come. That’s when you get to see your work in proof – the whole book set in type, like a real book. That’s often when you realise if a section of dialogue is flat, a description jars the pace of the narrative, or the story is moving too fast.

That’s when you feel like a sculptor, too, working happily on clay. It’s still yours to shape.

In The Bellini Card Yashim’s old friend Palewski, Polish Ambassador to the Sublime Porte (the Ottoman Court) is sent to Venice to track down a lost painting of Mehmed II.

I examine the proofs and I wonder – does Yashim enter this story the way I want? It’s clear, on this printed page: yes, it works. It makes me smile.

Just a few others have read The Bellini Card. And they smiled, too.