Speaking of orientalists (see previous blog), Sotheby’s have a sale of Orientalist paintings on April 24th in London. The link is at the end of this post.

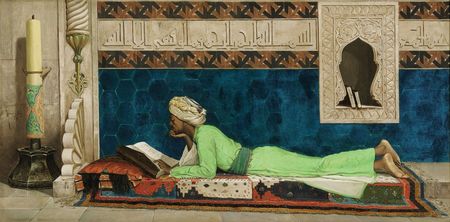

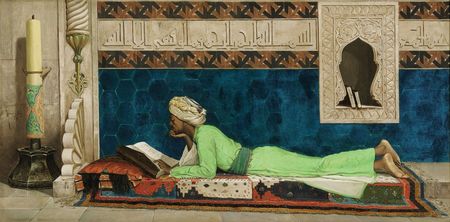

The star of the sale, to my mind, is Osman Hamdi Bey’s The Scholar: it could be Yashim’s young friend Kadri, from An Evil Eye, continuing his studies.

The estimate is £5 million.

If it’s too short notice to free up that amount, why not John Frederick Lewis’s A Halt in the Desert?

Lewis was not the first English artist to go East, but he was unusual in settling in Cairo for ten years from 1840, where he quietly worked on his sketch books. The British were about to fall in love with the Middle East. For one thing it was actually quite easy to go there by the 1840s, so that the sort of journeys which Byron had made so much of became almost everyday. David Wilkie, it’s true, didn’t make it home: his death aboard ship was commemorated in Turner’s Peace – Burial at Sea. Richard Dadd came home only to murder his own dad, afterwards pursuing his career inside Broadmoor; but others – like David Roberts – managed to lash themselves around the sites in short order. Even Edward Lear was able to roam from Albania to Petra (‘striped ham’, he noted) and get home safely. There is a good Lear in the sale, too. By the 1860s you could visit Palmyra with Thomas Cook.

Travellers by then could contrast the warmth and personality-based governance of the Ottomans with the repressive machinery of centralised government represented by Russia. After fighting the Ottomans in the cause of Greek independence, the British (and the French) tried to prop up the Sick Man by any possible means; British forces saw off an Egyptian incursion into the sultan’s dominions in 1840 (see An Evil Eye) and, famously, fought alongside the forces of the Sultan in the Crimea; some historians go so far as to describe the Ottoman Empire as a British protectorate in all but name. Echoing the spirit of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s observations in the previous century, some observers compared eastern freedoms favourably with the industrial slavery of Victorian England.

Lewis was not alone in trying to convey the dignity of Ottoman civilisation, partly by his emphasis on craftsmanship over soulless machine products (although by the 1840s, Europeans were unwittingly cooing over Manchester cottons on sale in the bazaars of Constantinople, fully in the belief that they had stumbled over a cache of exquisite native prints). There was a receptive audience for this stuff at home. Thackeray wrote: ‘There is a fortune to be made by painters in Cairo…I never saw such a variety of architecture, of life, of picturesqueness, of brilliant colour, of light and shade. There is a picture in every street, and at every bazaar stall.’ Lewis, whom he championed, really did it best: he may have recycled the same stuff for 25 years after he came home, even trying the patience of Ruskin, who had first encouraged him into oils, but he did it with a shy sense of irony.

Both in The Carpet Seller and in Interior of a Mosque, Afternoon Prayer (The ‘Asr) he renders a disguised self-portrait, once as the carpet dealer, the other as an old military man about to pray, which seem to exude a private yearning for fellowship with a world he could, when all is said and done, only watch from the outside. I like this one, A Harem Scene, Cairo, for the detail:

Lewis and his wife had no children. They never went out to parties, he wrote very few letters, and after all the apparent excitement of Cairene life he seems to have lived a life of quiet and blameless activity with his brushes in Walton-on-Thames, part of which, I am sure, can be glimpsed out of the window of his harem picture. His wife modelled for some of the decorous odalisques. Called upon to speak after dinner at a gathering of watercolourists, he apparently gazed silently at the ceiling and then sat down.

Not many painters do so well.

http://www.sothebys.com/en/catalogues/ecatalogue.html/2012/the-orientalist-sale#/r=/en/ecat.fhtml.L12100.html+r.m=/en/ecat.grid.L12100.html/0/15/lotnum/asc/?cmp=L12100_0412_2_ECATexample/

This is Gentile Bellini’s 1501 Turkish Painter, in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston

This is Gentile Bellini’s 1501 Turkish Painter, in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston