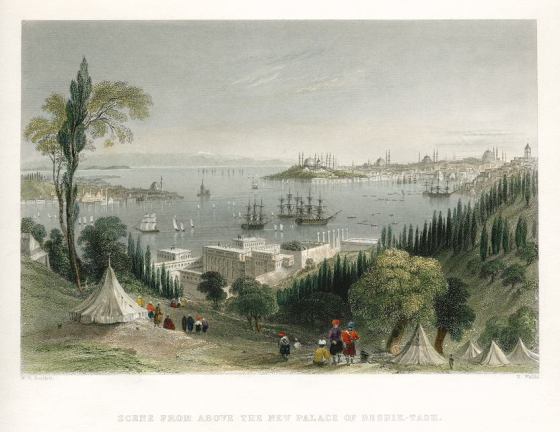

Istanbul residents have always treasured their green spaces.

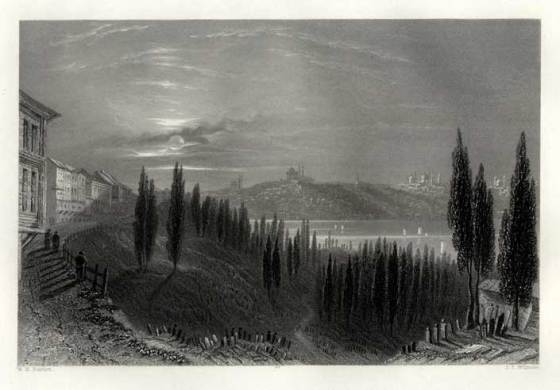

This was, once, a city of trees – ornamental cypresses in its graveyards, fruit trees in its gardens, the banks of the Bosphorus ablaze with Judas trees blossoming in the Spring. On the shore of the Golden Horn, on the Pera side, there grew an enormous plane, cut down on the sultan’s orders to clear the approach to the Galata Bridge.

Long before Istanbullu united to preserve the trees of Gezi Park and, by extension, to protest against the increasingly autocratic actions of Prime Minister Erdogan, I’d imagined a similar scene. In 1840, in The Bellini Card, Yashim encounters a crowd murmuring against the destruction of the great plane. The extract below is from that book, in which Yashim’s adventures take him from Istanbul to Venice.

Prime Minister Erdogan, unlike the sultan, is democratically elected, and seems to have done Turkey a great deal of good. All the more reason, then, to regret that he’s unwilling to enter into the kind of negotiation that a complex society like Turkey deserves. Liberty cannot mean majoritarian rule, as JS Mill pointed out, and there are voices and attitudes in Turkey’s modern society that should be handled with respect. As Norman Stone pointed out in yesterday’s Evening Standard, Erdogan is dangerously like another prime minister who after ten years in power came to believe that their will was identical to the will of the country. Mrs Thatcher’s term ended in ignominy.

One lesson that can be drawn from Ottoman history is that if the people require tribunes, so do their rulers. For many centuries the janissaries, despite their growing licentiousness and arrogance, performed that function: soldiers, who dominated civic society, could now and then express the popular mood. Their method was to overturn their great regimental cauldrons, and beat on them with spoons: the terrible sound of the janissaries in mutiny drifted from the barracks to the palace, and the sultan took note. Then in 1826 Sultan Mahmud II destroyed them, to a man.

Today, housewives in Beyoglu bang their pots and pans together at their windows. But Erdogan doesn’t seem to be listening.

Once the janissaries were eradicated, Mahmud and his successors were less beholden to the people. They furiously modernised the Ottoman Empire, running roughshod over popular disquiet, and collapsed unlamented in a puff of smoke at the end of World War I.

The Janissaries had their own tree, and their own traditions – and they, like the empire they served, are gone. Erdogan – like Mahmud II – still wants his mall.

Here’s the extract from The Bellini Card: note the detachment of troops in reserve.

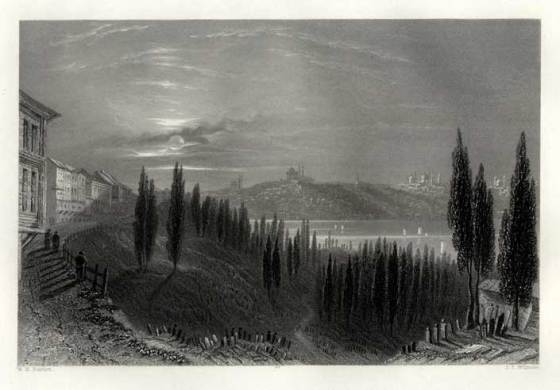

Yashim walked slowly back to the Golden Horn, taking the steep and crooked steps that led from the Galata tower.

He was about halfway down when he became aware of a strange sound, an unfamiliar murmuring from the shoreline below.

From the lower steps he gazed out over a crowd gathered around the gigantic plane tree. Its branches cast a deep pool of shade over the bank of the Golden Horn, where the caique rowers liked to sit on a sweltering day, waiting for fares. The lower branches of the tree were festooned with rags. Each rag marked an event, or a wish – the birth of a child, perhaps, a successful journey or a convalescence – a habit that the Greeks had doubtless picked up from the Turks, and which satisfied everyone but the fiercest mullahs.

Yashim heard the distinct rasp of a saw; looking closer, he realised that there were men in the tree. There was a sharp crack, and one of the branches subsided to the ground: the crowd gave a low groan. He scanned the faces turned towards the great plane: Greeks, Turks, Armenians, all working men, watching the slow execution with sullen despair; some had tears running down their cheeks.

Two swarthy men in red shirts started to attack the fallen branch with axes, stripping away the smaller growth: Yashim recognised them as gypsies from the Belgrade woods. They worked swiftly, ignoring the crowd around them. Out of the corner of his eye, Yashim caught a sparkle of sunlight on metal: a detachment of mounted troops was drawn up beyond the tree. He hadn’t noticed them. Perhaps the authorities had expected trouble.

He looked carefully at the crowd. Most of them, he guessed, were watermen for whom the felling of the tree was a harbinger of bad times to come: what would become of them, when people could walk dryfoot between Pera and old Istanbul? But it was also the loss of an old friend which for centuries had sheltered their members from the heat and the rain, which had accepted their donations, brought them luck, sinking its roots deeper and deeper with the passing decades into the rich black ooze. No-one had turned up to witness the destruction of the fountain: that, in the end, was only a work of man. But the plane was a living gift from God.

A second branch, thirty feet long or more, fell with a crack and a snapping of twigs, and the crowd groaned again. For a moment it seemed as though it would surge forward: Yashim saw fists raised, and heard a shout. Someone stepped forward and spoke to the woodmen, still hacking at the first branch. They listened patiently, staring down at the tangle of twigs and branches at their feet; one of them made a gesture and both men resumed their work. The man who had interrupted them turned back and pushed his way out of the crowd.

Yashim watched him: a Greek waterman, who stumped away to his caique drawn up on the muddy shoreline and stood there, looking up at the sky.

Yashim followed him down the steps.

‘Will you take me across to Fener, my friend?’

‘I never thought I would live to see this day, efendi.’ The Greek hitched his waistband, and spat. ‘I will take you to Fener, or beyond.’

As they pulled away, Yashim turned his head and saw that the woodmen were still at work. Two more branches had fallen, and the tree looked misshapen; he could hear the rasp of the saw and the toc toc of the woodman’s axe. A team of horses were dragging away the first bare branches.

The rower pulled on his oars, muttering to himself.