‘Astonishingly colourful and provocative history.’

Years ago I was on a train, reading The Independent, when I suddenly blushed. My heart raced. Without warning, I had come across a review by Jan Morris of my Ottoman history, Lords of the Horizons. She described it, among other things, as ‘a high-octane work of art,’ and I remember the jolt it gave me in the carriage, and the effort I made not to stand up and share my excitement with my fellow-passengers.

I suppose I am less excitable and more philosophical now, but I’m grateful to the crime novelist Abir Mukherjee for drawing my attention to a new review in The Times for the same book, in audio format. Abir’s first historical crime novel, A Rising Man, is set in Calcutta in 1921, in the days of the Raj, and if you are looking for a new historical detective series to devour, look no further. A Necessary Evil came out last year. I’ve just got my copy of Smoke and Ashes and I urge crime fans to do the same! Mukherjee is really good.

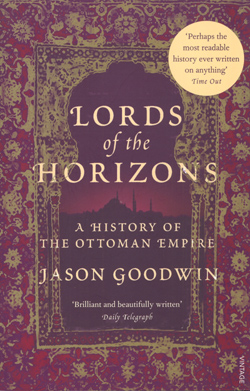

So Lords of the Horizons: A History of the Ottoman Empire, read by Grahame Edwards, is The Times on Saturday’s Audiobook of the Week, hurrah! The review is by Christina Hardyment:

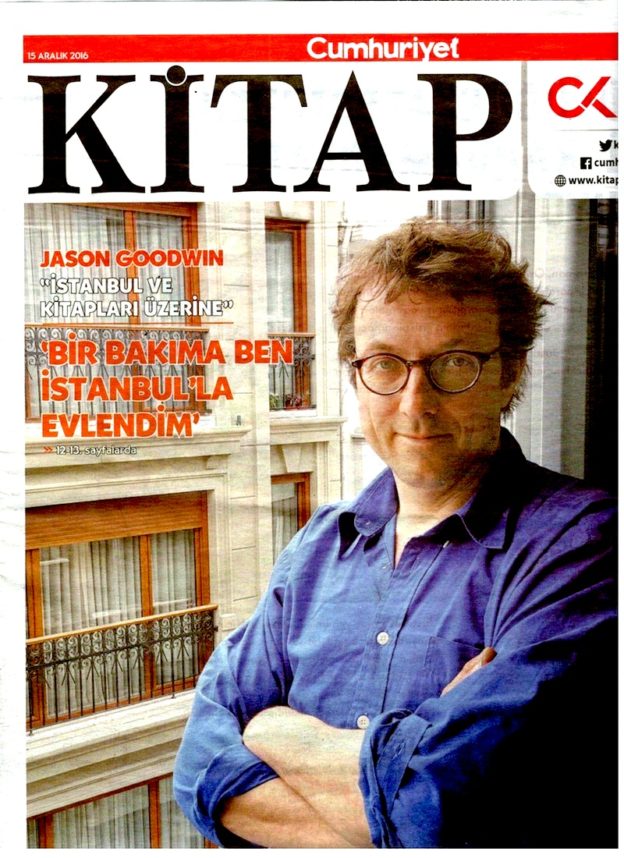

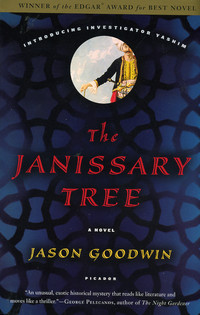

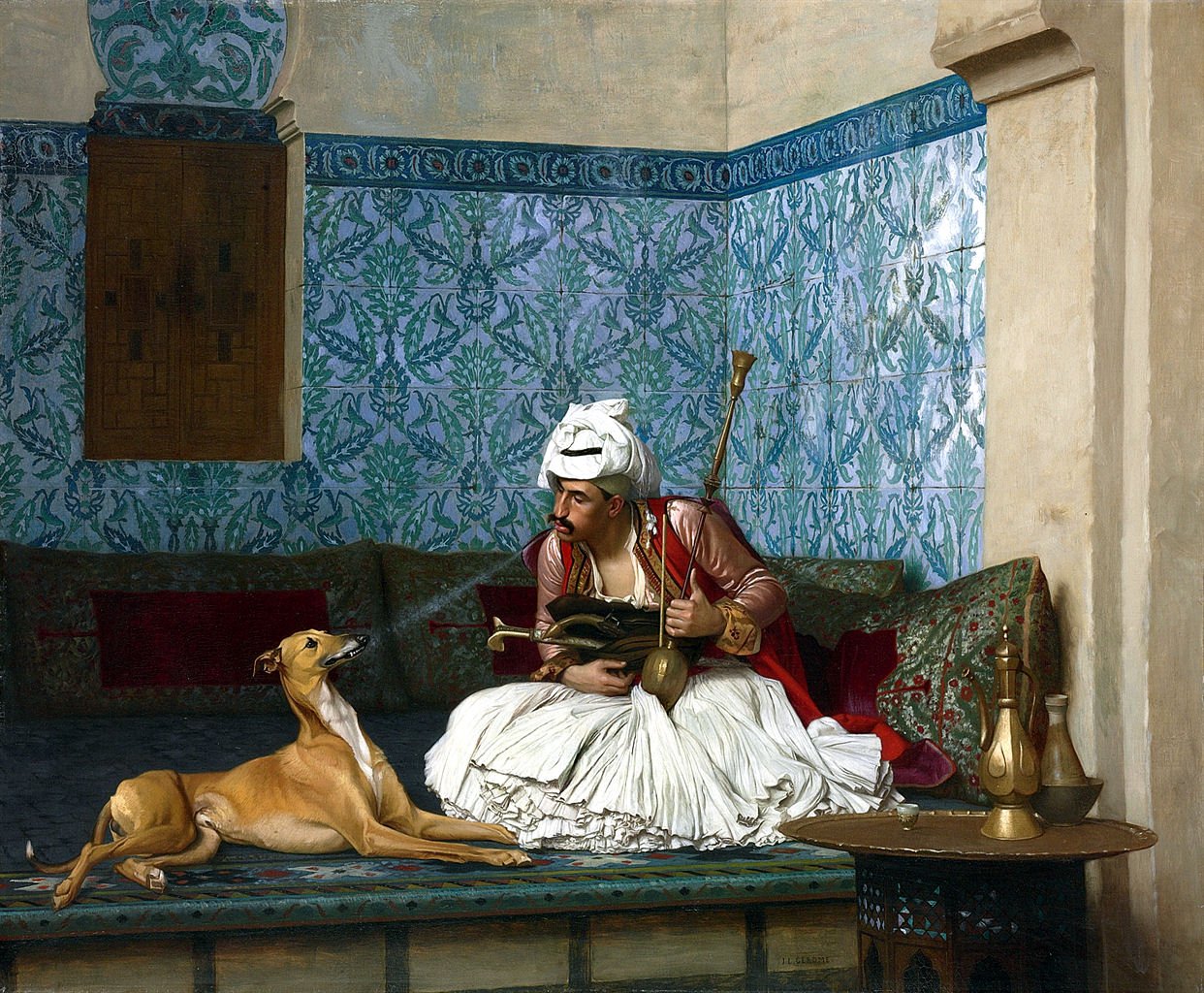

Jason Goodwin specialised in Byzantine history at Cambridge in the 1980s, walked there (On Foot to the Golden Horn) in 1993 and wrote this award-winning history of the Ottoman empire in 1998. His five excellent historical mysteries set in Istanbul in the 1830s star the gourmet eunuch detective Yashim; The Janissary Tree and The Snake Stone were superbly read by Andrew Sachs. Now at last we can listen to his acclaimed history.

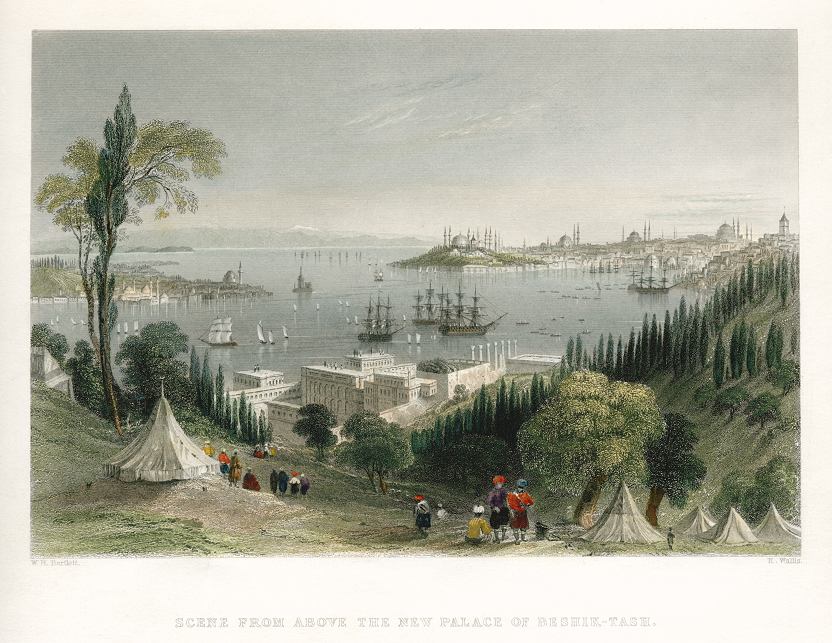

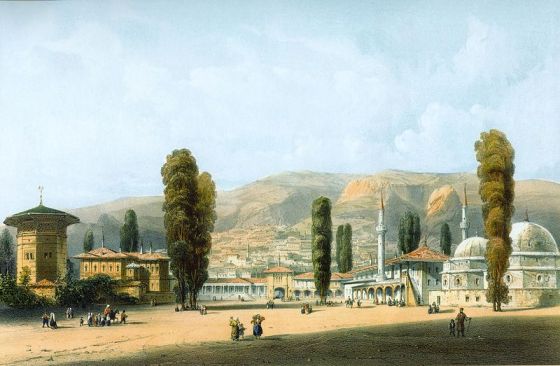

It is a rewarding, but challenging experience. Like Theodore Zeldin’s histories of France and Jan Morris’s accounts of Venice, Goodwin prefers themes to eras, proceeding crab-wise rather than chronologically. We glimpse such fascinating characters as Suleiman the Magnificent’s charismatic wife Roxelana (whom Titian painted), but then whirl away into art and architecture, imports and exports, religious toleration and brutal executions.

The narrator Grahame Edwards lapses after a while into a regular sing-song that makes concentration difficult. But spread out a map of the Ottomans’ vast territories, google images of their glories and persevere; this astonishingly colourful and provocative history is well worth the effort.

The reading lasts 12 hours and 42 minutes, and the audiobook is available here:

http://www.audible.co.uk/pd?asin=B07B3T42WV&source_code=AUKORWS03211890HU

BUT I have three copies of the audiobook to give away – and I’ll send the secret code to the first three people who email me at yashimcooks@gmail.com with the words LORDS OF THE HORIZONS in the title – and tell me which year Constantinople fell to the Turks.

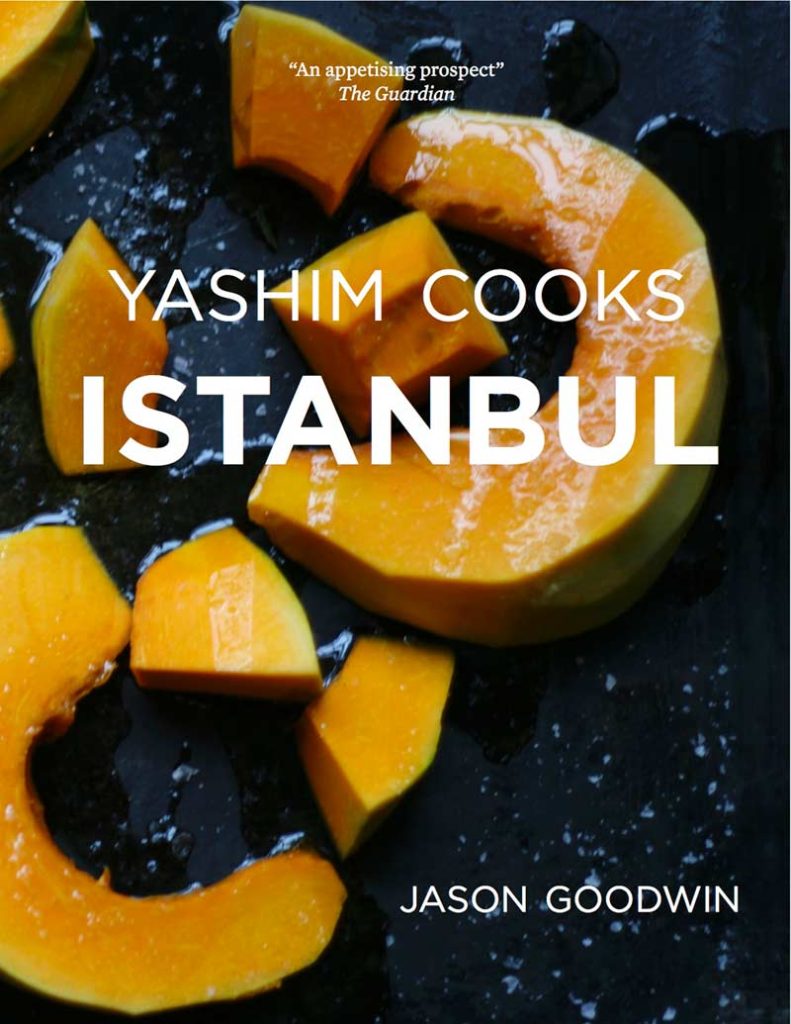

In other news, the 2nd UK edition of Yashim Cooks Istanbul: Culinary Adventures in the Ottoman Kitchen has arrived, and is available for a mere £12.99, identical to the 1st edition, hardback and beautifully illustrated, with nearly 100 recipes inspired by Yashim’s own friends, travels and adventures in Ottoman lands – and in Venice, Istanbul’s Mediterranean alter ego.

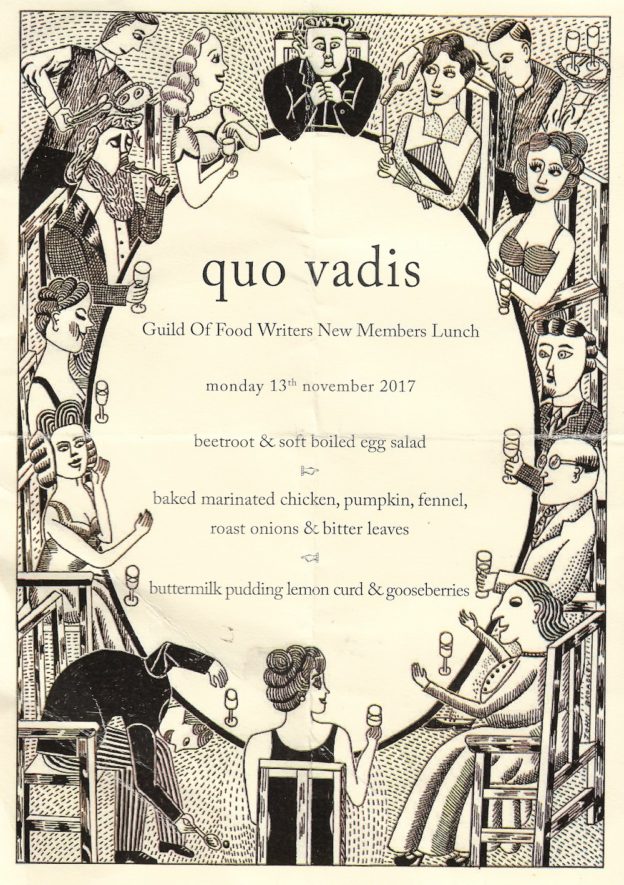

The judges at the Guild of Food Writers’ Awards described it as “A highly unusual book, which blends fiction with recipes and whisks you away to this exotic world as though on a magic carpet ride. Evocative, captivating and a treat to read a book that breaks new ground in the field of cookery writing.”

It has dozens of five star reviews on Amazon. If you reviewed it yourself, many thanks!

I’m writing a weekly column for Country Life Magazine, called Spectator. It’s on the back page, above the cartoon Tottering-by-Gently by Annie Tempest, and so far it has dealt with such matters as Russians in Dorset, old ladies, evensong, Marseilles tarts, historic architecture, and power cuts. You can read back numbers here: http://www.countrylife.co.uk/author/jasongoodwin

And finally, I’m judging the HWA’s Non-Fiction Crown 2018, and dozens of jiffy bags arrived this week containing incredibly interesting-looking history books to be consumed over the next two months or so. I hardly know where to begin. If you have read and would recommend any particularly outstanding history, published in the UK in the last twelve months, do let me know and I’ll try to call it in.

‘When you read a historical mystery by Jason Goodwin, you take a magic carpet ride to the most exotic place on earth.’ New York Times.